Pelizwa’s story tells us how it was during apartheid in South Africa. Black children were treated badly, went to poor schools and had to live separated from their parents:

“I live in Khayelitsha, outside Cape Town in South Africa. I asked my mum and my Gogo (gran) to explain what apartheid was. You see, there is no apartheid in my life. There is nothing I cannot do just because I am black.”

My gran’s story Gogo (gran) says she came to Cape Town from the Transkei, a poor ‘homeland’, which was what the apartheid government called the areas where they forced the black people to live. In those days all black people had to carry passes if they left the ‘homeland’. This pass gave them permission to move around in white people’s areas. My Gogo did not have this pass, but she took a bus to Cape Town and found work with a white lady. “Every morning I left the township where I lived at six o’clock, because after eight the inspectors checked everybody’s passes on the bus. If you didn’t have a pass, they would beat you and put you in prison. Then you’d have to go back to the Transkei to starve,” recalls Gogo.

Like a dog

“One day, I saw the pass inspector through the window. He was going from house to house checking the maids’ passes. I phoned the lady I worked for. She told me to hide in a cupboard until she got there. Then I heard her telling the inspector that there was only a dog inside.”

That’s how it was in those days. We carried the white people’s babies on our backs and raised them, while our babies had to stay behind in the ‘homeland’.”

My mother’s story

My mother grew up in the Transkei with my Gogo’s mother, my great grandmother, who died while Gogo was working for the white people. Then my mother stayed with neighbours in the Transkei. She only saw her mother at Christmas, when Gogo used to bring her the white children’s old clothes. My mother told me about when she was a little girl in the Transkei: “I was never close to my mother in the way that you and I are close. When my own Gogo died I was just like an orphan. I knew that my mother was looking after the white children far away. Then, when I was eleven, she came to get me and since then I’ve lived with her in the township.” “One day, I went to work with my mum to help her polish the lady’s silverware. When we got to the train station in the white area, I saw signs everywhere that said: ‘Whites Only’. They were on buses, doors, shops, benches and all kinds of places. I thought it was so strange that white people did not want us blacks to sit on their benches. My mother said that we should never disobey these signs because the police or the white people would beat us. My mother also forbade me to drink from any of the cups in the lady’s kitchen. She said that she would be fired if I did. Instead I drank water from a jam jar that my mother cleaned for me.”

Angry teenager Peliweza says: "It was during this time that my mother first heard about Nelson Mandela. She saw a photograph of black men running away from the hostels for men who worked in the gold mines.

Gogo explained that it was because the police had come to beat the men because they had protested against the apartheid pass laws. Gogo said that my grandfather worked in the mines and this was why we never saw him. These mine hostels were like prisons for slaves. Gogo said that Mandela was the chairman of the ANC, African National Congress, which organised these protests.

My mother told me that she experienced all these terrible things that apartheid did to children while she was growing up, so when she became a teenager she was very angry. In 1976, she and thousands of other children protested against inferior education for black children. Their schools were very poor and overcrowded.

“We were so angry that we decided to fight with everything we had to stop this apartheid. Early on the morning of 16 June 1976, my friends and I huddled together behind our shack and made bombs from sand, petrol, matchsticks and a piece of cloth that we put into a big coke bottle.”

My cousin’s storyMy cousin Babalwa is much older than me. Her mother was a member of the ANC and often left Babalwa and her brothers and sisters home alone to go to secret meetings, because the ANC was banned. Babalwa says: “When she went to a meeting she told us not to open the door to anyone. We were afraid, because we knew how many people just disappeared because the police took them. What if they came and asked us where my mother was? If we didn’t tell them, would they put us in jail? We knew so many children who had been beaten and thrown in jail when they didn’t do what the police wanted them to do.”

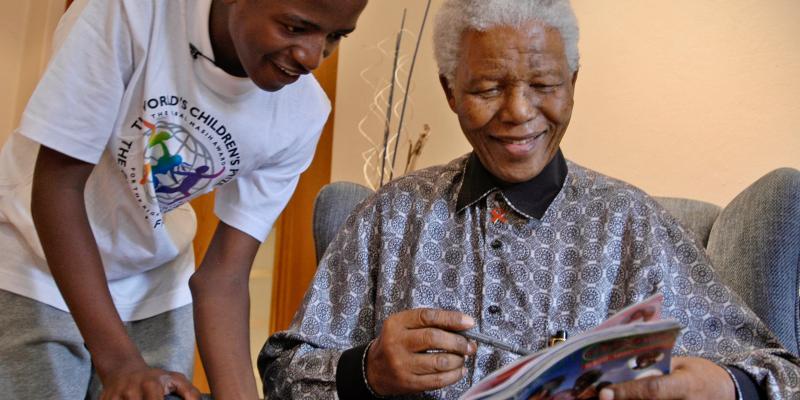

My storyI did not riot or hide away or lose my mother in apartheid. By the time I was born, Mandela had been released and the ANC was no longer banned. I can grow up enjoying the freedom that my parents and Mandela fought for. Nelson Mandela is also my hero because he cared about everyone who is HIV-positive. He spoke up for children and families who have been affected by the virus and because he was so famous, everyone listened when he talked.

Related stories

Långgatan 13, 647 30, Mariefred, Sweden

Phone: +46-159-129 00 • info@worldschildrensprize.org

© 2020 World’s Children’s Prize Foundation. All rights reserved. WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE®, the Foundation's logo, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PARLIAMENT®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S OMBUDSMAN®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRESS CONFERENCE® and YOU ME EQUAL RIGHTS are service marks of the Foundation.