Yen is often shy, but when she’s dancing or practising karate she feels self-confident and strong. Her grandma brought Yen to Minh Tú when her dad left the family and her mum was too ill and poor to look after her.

It takes ages to choose the music. Yen argues with her friends Nga and Phouc about which South Korean pop star is best. In the end they agree on more traditional Vietnamese music and start dancing the ‘hat dance’ to the rhythm of the music, while making special movements with their hats.

There are posters of South Korean pop artists above Yen and her friends’ beds. And there are some famous musicians on the inside of Yen’s cupboard too.

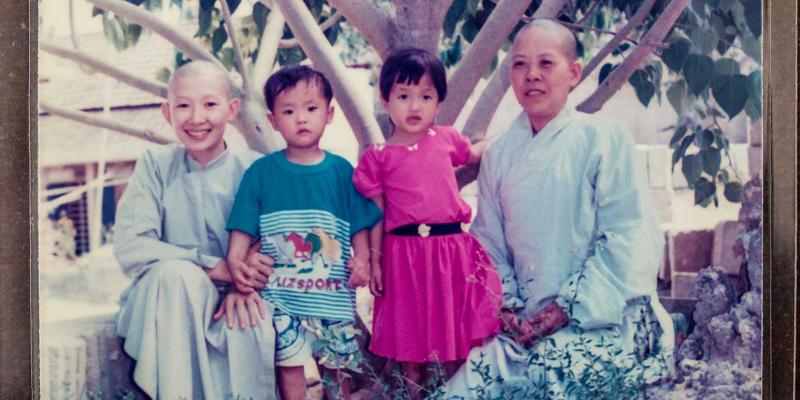

This is where Yen retreats to – the world of music and dance – when she wants to get away from it all. She’s been living at the children’s home at Duc Son pagoda since the age of seven. She loves the nuns and her friends, but she often dreams of a life somewhere else.

Sad day

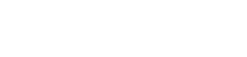

It was a sad day when Yen first arrived at the pagoda. Her dad had disappeared, and her mum Vinh was suffering from a serious mental illness. That’s why Yen’s grandma had been looking after her. The family was poor, and it was hard for grandma to care for both her daughter and granddaughter. She took Yen by the hand and went to Duc Don pagoda. There she asked Minh Tú to take care of Yen.Discovers dance

“It was hard. I was sad, but the nuns were kind and I soon made lots of friends,” says Yen. She got to start school. It was exciting, but scary with all the new faces.“Would you like to dance?” asked one of the nuns.

“I can try,” replied Yen.

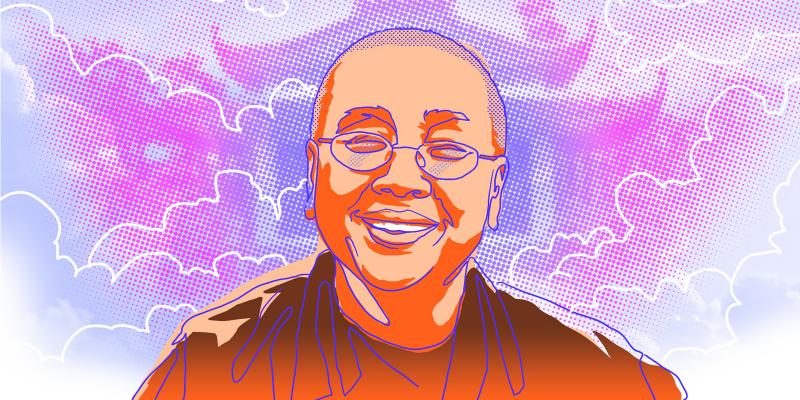

The nuns helped Yen and her friends to put their hair up in pretty styles and put make-up on, so they almost looked like dolls. They wore Áo dài, lovely silk dresses.

When the music started, Yen couldn’t keep still. She just felt she had to move. She watched the nuns, who showed her how to move in time with the music.

Soon the girls were performing for the other children. It was exciting, and they were nervous. But when the music started, Yen didn’t see the audience. She only heard the music, and followed the dance steps she had learned.

“I feel free. I’m not bothered by the audience,” said Yen.

She told the nuns how much she loved dancing. She practiced every week with her friends. She dreamed of getting into dance academy and becoming a choreographer.

Visiting mum

Yen often missed her mum and grandma. She knew they were out there somewhere, outside the pagoda walls.“I’d like to visit grandma and mum,” said Yen to Minh Tú one day.

“I understand,” said Minh Tú. “We can arrange it so that you get to meet them every New Year’s holiday.”

She explained to Yen that the most important thing was that she carried on going to school. There was no guarantee she could do this at home with grandma and mum.

“They don’t have much money because they can’t work,” said Minh Tú. Yen understood, but she was glad she’d get to see her family. Many of the other children at the children’s home didn’t have parents at all. But she did, even if they were ill and living in poverty. When Yen got to go out and visit her family she saw something other than the pagoda. She got to see the old city of Huế. It was huge, with lots of people and shops. As Yen grew up she started daydreaming more and more. When she wasn’t dancing, she started painting and doing karate.

On an adventure

Yen had several friends at school who lived in Huế with their families. They were always talking about parties and how they would go shopping on the weekends. It sounded exciting. One day, a school friend asked if Yen and some of the other girls wanted to come too. “It’s easy. Some of the older kids have told me how to do it,” said one of Yen’s friends at the pagoda.After dinner that day, Yen helped put the younger children to bed. Then she did her homework. She and her friends got ready for bed. When the lights were switched off and the nuns had gone to bed, Yen and her friends snuck out. There were ten of them. They got changed and tiptoed out through the entry gate. Down by the road they’d organised transport, which took them to a big shopping centre in Huế. They hung out there with their school friends, laughed and just talked while looking in the shop windows. It was exciting to do something forbidden, and it felt good to get away from the pagoda for a bit.

When they got home to the pagoda late that night, the nuns were waiting anxiously for them. They were not happy. Yen and her friends were sent straight to bed. The next day they had to kneel for a long time and think about what they had done.

“It didn’t matter. I love Minh Tú and the rest of the nuns. They are like my family and I’m never afraid when I’m with them. But I also want to be independent and do what I want. I can’t wait to be an adult,” says Yen.

Text: Erik Halkjaer

Photo: Jesper Klemedsson

Related stories

Långgatan 13, 647 30, Mariefred, Sweden

Phone: +46-159-129 00 • info@worldschildrensprize.org

© 2020 World’s Children’s Prize Foundation. All rights reserved. WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE®, the Foundation's logo, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PARLIAMENT®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S OMBUDSMAN®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRESS CONFERENCE® and YOU ME EQUAL RIGHTS are service marks of the Foundation.