Valeriu grew up in the countryside in an area where everyone was different, yet they managed to get along. He had lots of friends who looked different and spoke many languages. But when he was seven the family moved to a bigger town. Suddenly no one wanted to play with him anymore.

“On the first day in our new flat, mum told me to go out and play so she could clean in peace. I saw a girl in the yard with blond curly hair who looked friendly. I asked if we could play, but she replied: ‘I’m not allowed to play with gypsies because they’ve got lice.’”

Valeriu didn’t understand. He started crying and ran home to his mum. She stopped cleaning and sang him a song to cheer him up.

“It was about a brown bear who had to struggle to get along in a world full of white bears. Later, she made up her own song too, about how if you’re kind and you work hard, you’ll get along in life. She never let me blame any difficulties on the fact that I was Roma. She said: ‘You have to prove that you are good enough. And to be good enough, you have to be at least ten times better than all the non-Roma.’”

Racist stepfather

To Valeriu’s new neighbours, he wasn’t just an ordinary boy, he was a “dirty gyppo kid”. Even his stepfather, who wasn’t Roma, used to call him gyppo kid instead of Valeriu. The word gyppo was used by many to describe people from the Roma community, often as an insult.

“My stepdad hated Roma, just like others in Romania and many other countries have done for centuries. He had all the usual prejudices, like that Roma are dirty, lazy and thieving. In fact I never could understand why he married a Roma lady! But he liked to drink, so maybe he felt at home with the many alcoholic men in our family.”

Clean and well-fed

Valeriu’s mum worked hard in and outside the home, so that Valeriu and his two older stepsiblings would have a good life.

“We were poor, but we always had clean clothes and never went hungry.”

When the stepdad drank, he became violent.

“He often said he was going to kill us all, but he mostly beat my mum. Sometimes she hit back, with the dustpan, or threatened him with an iron bar to make him stop. I often got between them to protect her. But we didn’t stand a chance against dad, he was much bigger and stronger than we were. And there was no point in complaining to the police because almost all men beat their wives and children, even the policemen! It was accepted in society. My aunt even told mum she should be grateful that he beat her, because it meant that he loved her!”

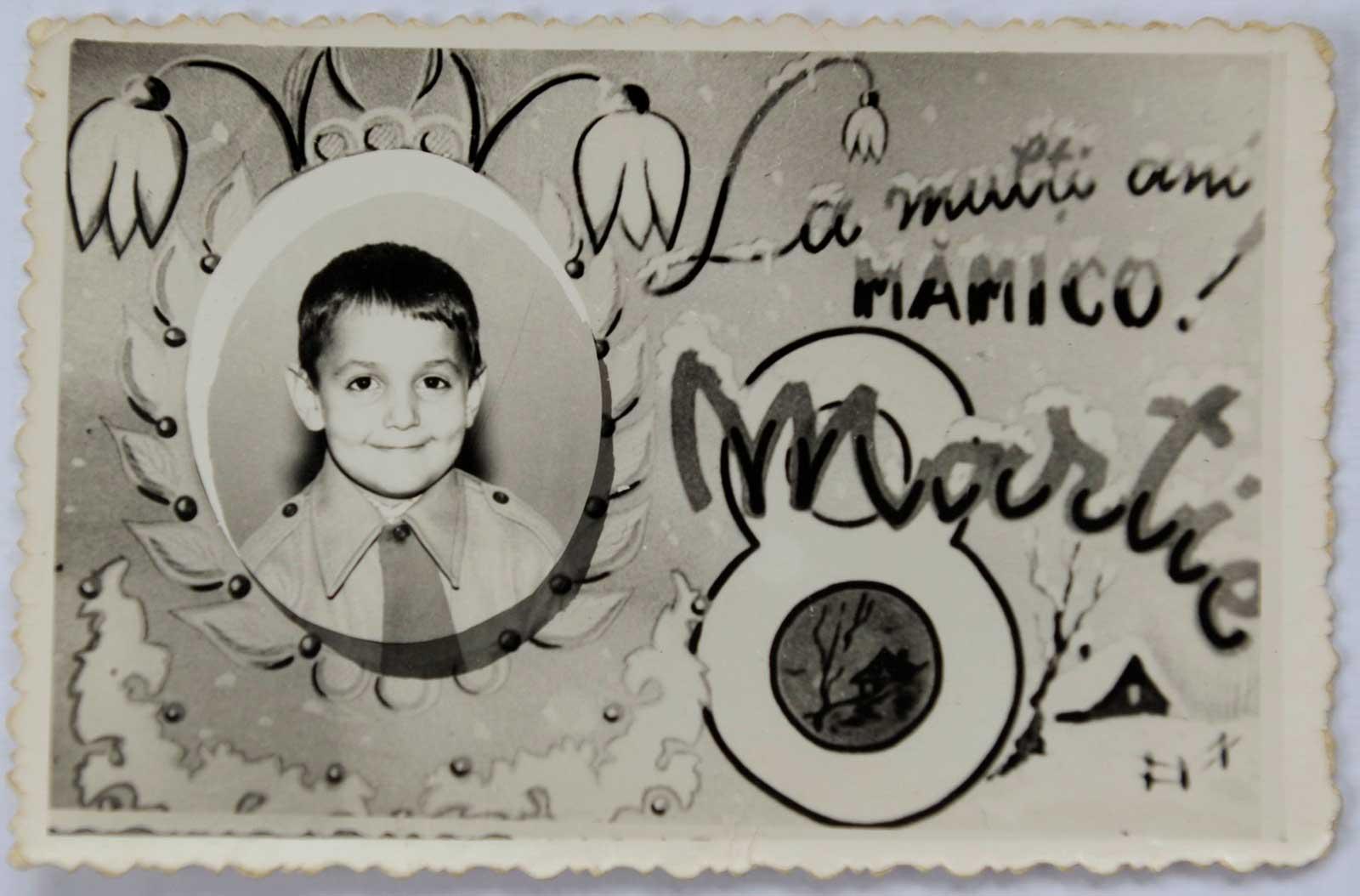

Valeriu’s Mother’s Day card to his mum.

Left to own devices

Valeriu soon realised that most of the parents in his new neighbourhood didn’t allow their children to play with Roma children.

“It was good in a way,” says Valeriu. “I didn’t have anything to do, so I wandered around and found a library. The lady who worked there didn’t have any children of her own, so she looked after me and showed me loads of great books. I read adventures, history and about other countries – and I learned a lot.”

Valeriu also made a friend – an abandoned dog.

“It was a bit bad-tempered at first, but I realised it was in pain from an inflamed tooth. I got the dog to open its mouth and managed to take out the bad tooth. After that, the dog was my faithful friend.”

When Valeriu was 12, he fell in love with a girl whose parents didn’t like Roma people either.

“It was after the summer holiday, so I was even darker than usual. I remember scrubbing myself with a hard brush to try and make myself whiter, but of course it didn’t help!”

As a boy Valeriu extracted an infected tooth from an abandoned dog, that probably look as as this dog in modern day Bucharest. Through his action, Valeriu gained a faithful friend.

Valeriu actually prefers basketball to football, but the children in Ferentari and other parts of Bucharest disagree!

Two jobs

Until recently, Valeriu had two jobs. From Monday to Friday he was working in Brussels in Belgium, at the European Commission on Human Rights. Valeriu had been appointed Special Representative of the Secretary General for Roma Issues. Every weekend, Valeriu went home to work at the Education Club and the sports center in Ferentari, together with his family and friends.

“None of us got paid. My salary from the European Commission was enough. We just did what we could,” says Valeriu.

Dreams for the future

Now Valeriu has decided to give up his well-paid position and come back home, to work full time on what he feels most strongly about.

“I will continue my work with the children in Ferentari. I also want to start a company, because the children who grow up here need somewhere to work. I’ve got lots of ideas that I want to make a reality together with the children in Ferentari.”

Related stories

Långgatan 13, 647 30, Mariefred, Sweden

Phone: +46-159-129 00 • info@worldschildrensprize.org

© 2020 World’s Children’s Prize Foundation. All rights reserved. WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE®, the Foundation's logo, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PARLIAMENT®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S OMBUDSMAN®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRESS CONFERENCE® and YOU ME EQUAL RIGHTS are service marks of the Foundation.