“I’m glad that we have a great school where we live,” says Wade, 14.

“In lots of other reserves they have to travel long distances to get to a shop or be able to go to high school.”

“It was scary, I was worried about my dogs.”

Despite the wild bears, Wade and Odeshkan love living close to nature and being able to fish and hunt.

“When the lake freezes in winter, we go skating and play hockey on the ice,” says Wade. He and Odeshkan love ice hockey, Canada’s national sport. Wade wants to be a professional ice hockey player or personal trainer. Odeshkan, who has had several film roles, wants to be an actor or a politician.

Self-governing

The boys are members of the Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg Nation, which governs its reserve. Instead of a local government commissioner, they have a Chief and a Council that makes the decisions.“We study the usual subjects at school, but we also learn about our culture and our language,” says Wade.

There are lots of healing herbs and trees growing on the land around the school. Wade found out about these from his great grandmother Barbara and great grandfather Morris.

“They teach me to speak Algonquin, and about our ceremonies. Some of the older people burn cedar, sage or tobacco every day to cleanse themselves with the smoke in a practice called smudging.”

When Odeshkan’s family goes hunting, they always place a little tobacco on the ground and say a prayer if they shoot an animal.

“According to our tradition, everything and everyone is treated with love and respect. We thank nature and the animal for giving us food,” Wade agrees.

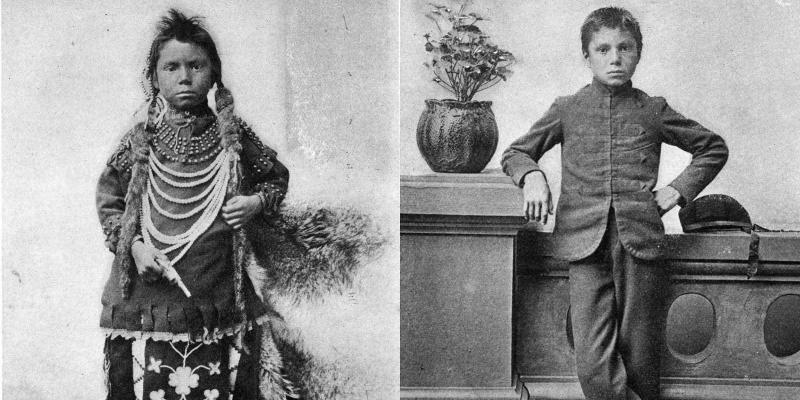

Lost knowledge

Many of the boys’ older relatives were sent to residential school when they were little.“The schools were supposed to ‘kill the Indian in the child’,” says Wade.

“When my relatives came home, they couldn’t even speak to their parents. I’d feel completely lost. Some people say: ‘Forget that, it was a long time ago.’ But I’m never going to forget. I’m grateful that they survived, because I wouldn’t be here otherwise.”

“I just don’t understand how they could do that to children,” says Odeshkan. “Everyone in Canada needs to learn about Indigenous peoples and our history. If we work together, we can build a better future. But I’m still proud that our people managed to keep our culture and our language alive. We’re still here!”

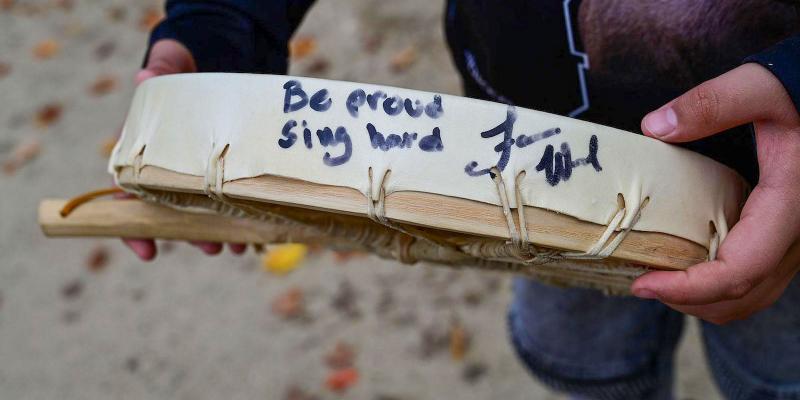

Dancing and drumming!

“I love dancing and drumming, and I take every opportunity to share our culture”, he says.Text & Photo: Carmilla Floyd

Långgatan 13, 647 30, Mariefred, Sweden

Phone: +46-159-129 00 • info@worldschildrensprize.org

© 2020 World’s Children’s Prize Foundation. All rights reserved. WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE®, the Foundation's logo, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PARLIAMENT®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S OMBUDSMAN®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRESS CONFERENCE® and YOU ME EQUAL RIGHTS are service marks of the Foundation.