David was 16 when one of his gang friends shot at two guys on the street. Nobody was badly injured, and David wasn’t the one holding the weapon. Still, he was convicted of attempted murder and sentenced to life in jail, with no chance of freedom, ever.

David’s father was in and out of prison and he and his three younger siblings were raised by their aunt. Their mother came to visit sometimes. One day she took David’s younger siblings and disappeared. David was left behind, alone. At night he often lay awake thinking, ‘Why doesn’t she want me?’ He tried to make up all kinds of reasons, but nothing felt right. David’s cousins teased him because he didn’t have any parents. When he was seven, he asked his aunt why he couldn’t live with his mother. “Times are tough,” she replied. A few years later, when David was eleven, his mother came back and took him to Mexico. But she abandoned him again there. His father was hardly ever out of prison long enough for them to meet. David got used to the fact that his parents couldn’t take care of him.

A new family

David lived in the middle of a poor, dangerous area. His uncle was a gang member and David looked up to him. He also admired the gang’s style and their strong sense of unity. When he was thirteen, David asked if he could join the gang. “No, school is more important,” said his uncle. The other gang members thought he was too young as well. But David dropped out of school, and was finally allowed to be ‘jumped’ into the gang. That meant that he had to let two gang members beat him up badly for a few minutes. Then they gave him a gun and told him to be ‘ready for whatever’. David’s uncle was upset. “If you stay on this path you will end up in prison or dead.” That same year, one of David’s old classmates was shot to death in a gang fight. But by then he had started taking so many drugs that he couldn’t feel fear or sadness.The beginning of the end

The gang became the family that David had never had. When he wasn’t working with his uncle, who was a construction worker, he would hang out with his new friends day and night. One morning, they got into a fight with some boys from another area. One of the older gang members decided they should go back to David’s and get his gun.“This feels like a bad idea. Let’s not do this,” said David as he handed over the weapon. He was right. Not long after, his friend shot at the two boys and hit one of them. David was standing beside him and saw the boy fall. Later that day, he was arrested by the police.

Trial begins

The boy who got shot only sustained a minor injury, and he was able to leave the hospital the same day. But the shooting was still considered attempted murder, and it was decided that David should be tried in an adult court, although he was only sixteen. The prosecutor offered him a deal:

“If you agree to a life sentence you don’t have to go to trial and have the chance of getting out on parole after 25 years.”

But David said no. He didn’t know much about the law, but he hadn’t shot anyone, so why should he go to jail for 25 years?

David was held at the youth detention center for seven months, until the first day of his trial. At four in the morning, the youth detention center bus took him to court, shackled hand and foot. The defense lawyer gave him a suit to wear and told him to hide his gang tattoo. When David entered the court, he looked so young and thin that the jury, twelve men and women of different ages, seemed to feel sorry for him. But the prosecutor said:

“This little kid is not as innocent as he looks.”

Then he showed old police pictures of David and his tattoos. A gang expert testified and described David as one of the worst of the worst.

The jury’s decision

The trial lasted for a week and a half. Then the jury retired to deliberate. David waited alone in a small, cold, dirty cell. He shut his eyes tightly and said to himself:

“Be ready. This will be bad.”

After an hour the jury came back. David was brought back into the courtroom and saw his aunt, his mother, and his girlfriend sitting there. “I love you guys,” he said before a guard handcuffed him to the chair. One of the members of the jury stood up and read from a piece of paper: ‘Guilty’. David felt his insides turn to ice, even though he had been expecting it. The judge looked at him and asked if she should feel bad for giving him a harsh sentence. “You are so charming, and look so young and innocent… You look like a little angel.” Her nice words confused David. She paused and continued: “But that’s what scares me.”

The staff put a note on David’s cell door to check on him every half hour, to make sure he didn’t take his own life.

Tough sentence

The judge said that David would never get the chance to commit another crime. He was sentenced to three life sentences plus 20 years, with no chance of release. The sentence was automatically tougher because he was a member of a gang. David started to cry as he was led back to his cell. One of the guards, a big man with spiky hair, gave him two bits of chewing gum and said: “Don’t pay attention to her. You know who you are. And maybe you’ll get it overturned.” There were only two buses a day between the youth detention center and the court, so David had to wait for hours in the cell. He tried to sleep on the concrete bunk, but it was too cold. His defense lawyer came by briefly. He was annoyed. “I told you to take the prosecutor’s deal,” he said. When David got back to the youth detention center around midnight, everyone knew what had happened. The staff had put a note on his cell door to check on him every half hour, to make sure he didn’t take his own life.

No visitors

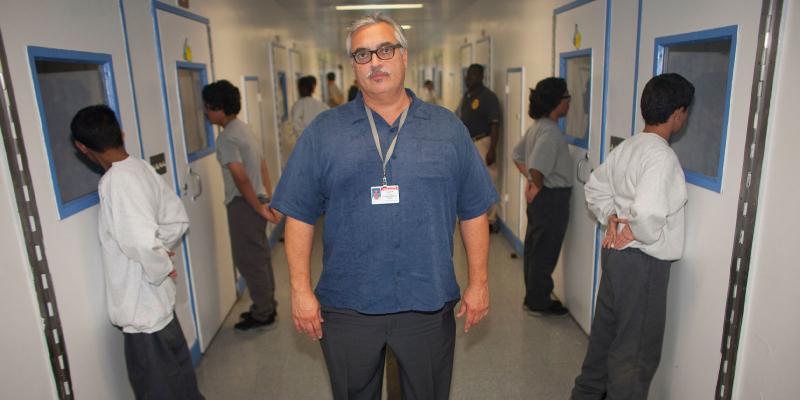

When David turned eighteen the youth detention center organised a farewell party. Then he was moved to one of California’s infamous adult prisons. “I was really scared,” he says now. “But I shared a cell with an older guy who tried to calm me down. He said, ‘You’re a youngster, your gang will look out for you. Just stay away from drugs, gambling and fights.’”Just a few weeks later, the prison was rocked by violent rioting between different gangs. Many were stabbed and beaten with weapons that had been smuggled in or made in prison. Both prisoners and guards were injured. Although most of the prisoners were not involved, all the inmates were punished by having visits and phone calls withdrawn for a year. David and the other prisoners were hardly ever allowed to leave their cells. “The guards called us ‘ghosts’ because we all turned so white in there, without any sunlight.”

Farewell to the gang

David has been sentenced to stay in prison until he dies. He hopes that the new laws that Javier has told him about might give him a chance to get out in 20 or 30 years. But for that to happen, he has to stay out of trouble. That’s why he has just moved to another part of the prison, for people who want to break free of gang life. It was a really tough decision. “My gang was my family for a very long time, and they looked out for me inside. But I was so tired of wearing a mask all the time. There was at least one stabbing every week. I didn’t like to see people hurt, and I didn’t want to hurt anyone. I want to live and maybe have a chance to meet my daughter one day. Even if it means breaking that bond with the gang.”Text: Carmilla Floyd Photos: Joseph Rodriguez

Related stories

Långgatan 13, 647 30, Mariefred, Sweden

Phone: +46-159-129 00 • info@worldschildrensprize.org

© 2020 World’s Children’s Prize Foundation. All rights reserved. WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE®, the Foundation's logo, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PARLIAMENT®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S OMBUDSMAN®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRESS CONFERENCE® and YOU ME EQUAL RIGHTS are service marks of the Foundation.