Javier Stauring was shocked the first time he visited a children’s unit at Los Angeles Central Jail. He found 14-year-olds in isolation in dark cells, almost 24 hours a day, for months at a time. Javier protested, but it wasn’t until two of the children tried to take their own lives that he was able to get the world around him to react.

It all started with politicians in California deciding that children who were suspected of serious crimes, such as armed robbery or attempted murder, had lost their right to be treated as children. Instead, they should be sent to an adult court and given sentences as tough as adults. The politicians introduced laws that meant that more children could be sentenced to life in prison, even if they were as young as 14. Many adults said, “If kids are old enough to do the crime, they’re old enough to do the time.”

Javier believed that children who committed serious crimes should be cared for by society until they were no longer a threat to other people or themselves. But at the same time, he was sure that with the right help, children could change. He had worked for many years as a visiting chaplain, a kind of counsellor. Javier listened to the children who were incarcerated in prison or youth detention centers, and talked about taking responsibility for their actions, and choosing a life without violence and crime. Almost all those he met had been subjected to violence and abuse throughout their childhoods. Javier’s belief was that they needed support, not punishment.

Politicians didn’t agree

But the politicians had the opposite view. They said, ‘Lock ‘em up and throw away the key’ and blamed their attitudes on their voters’ fears of violent children. Newspapers and TV news had long been aware that they gained more readers and viewers when they reported on children and terrible crimes. People found it exciting but also frightening. They felt safer when the politicians promised to lock the children up for ever.Prison instead of school

In the early 2000s, there were tens of thousands of children locked up in youth detention centers (‘prisons’ for children) in California, and hundreds of children had been sentenced to life in prison with no chance of release. For 20 years, all new laws regarding children and crime had moved towards tougher sentences. Millions of dollars were invested in building more and larger prisons – much more than what went to schools and crime prevention programs.

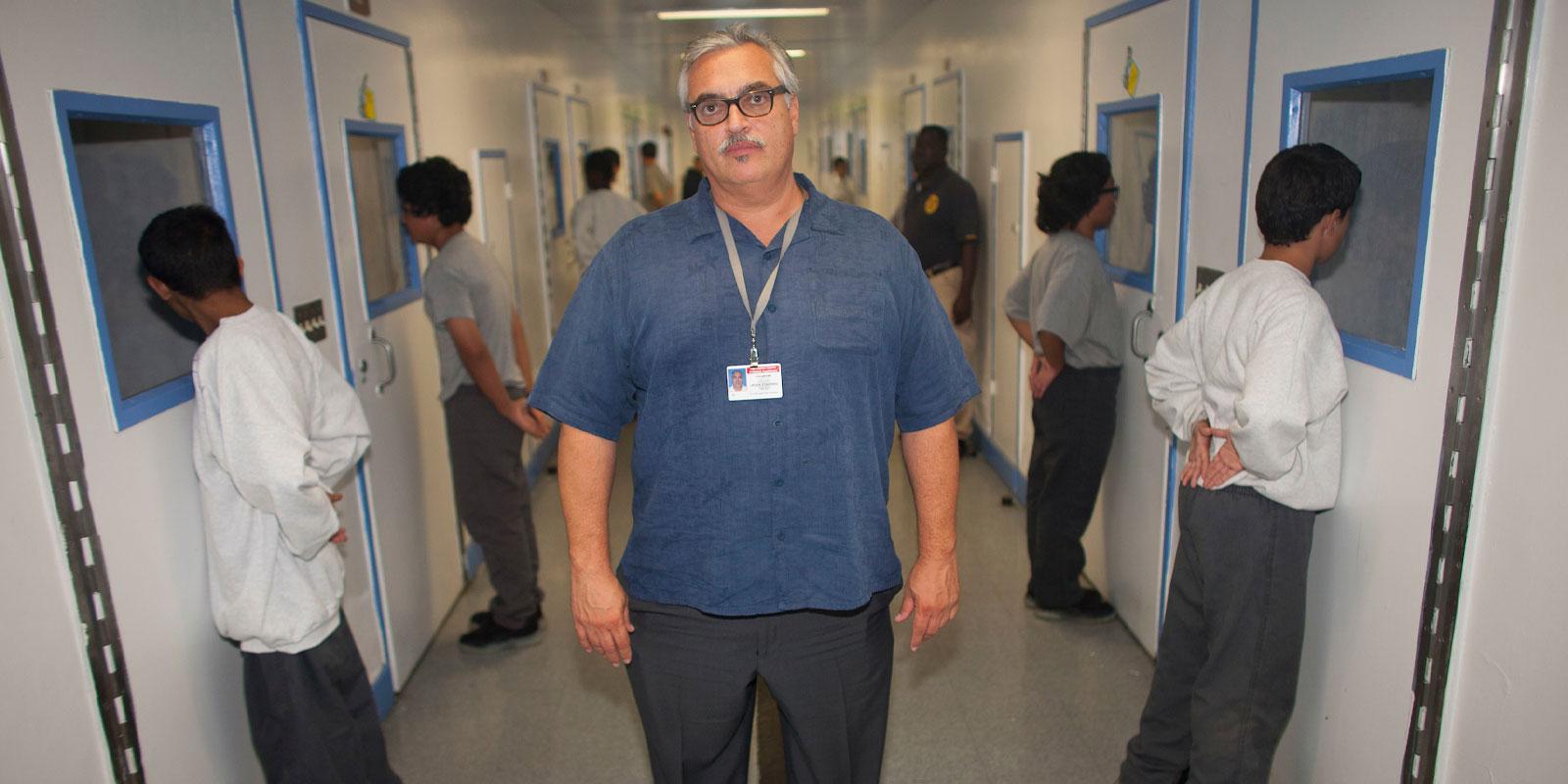

When children sentenced to life long sentences turn 18, they are transferred to maximum-security prisons for adults. Photo: Joseph Rodriguez

At the same time, schools started to call in the police for behavior that used to be dealt with through detention. Instead of contacting the parents, schools started calling the police when students skipped school or tagged the walls. Poor families were handed large fines, and youth detention centers became overcrowded. A high-ranking judge told Javier, “I have to go by the law, but what is happening is wrong. We punish kids for being kids, and give them no chance to grow out of it.”

Solitary confinement

One day Javier went to visit Maria, a teenage girl he had got to know at a youth detention center. She had gone with her adult sister, who used a screwdriver to threaten a woman for money. Maria had now been moved to an adult prison. Javier was curious, because neither he nor other advocates knew how children were treated there.

A guard took Javier through the long corridors and down lots of stairs to the solitary confinement unit. This unit, or ‘the hole’, was known to be the worst place in the whole prison. Only the most dangerous prisoners were brought here, as punishment if they had done something like attacking another prisoner or a guard. Javier was confused. What had Maria done to be brought here?

“If kids are old enough to do the crime they’re old enough to do the time.”

The guard stopped beside a long row of metal doors, and pointed to one of them. Javier peered through a small hole in the door and saw Maria, curled up on a bunk, right next to the stainless steel sink and toilet. Javier called to her. She got up slowly and stumbled over to the door, stick-thin and pale as a sheet, with her long hair hanging unkempt. “Why am I here?” she asked in a hoarse voice. “I’m cold.”

Nightmare in the dark

Maria had no blanket in the cell, just a thin plastic mattress. The prisoners in ‘the hole’ were often so lonely and desperate they wanted to die. That’s why they were not allowed bedclothes – in case they used them to hang themselves. Maria spoke to Javier through the food slot in the door. She had been brought straight from the youth detention center to the dark, windowless cell, early one morning. The only light came from the corridor, through the hole in the door. “I asked the guards why they didn’t turn on the lights during the day. They said, ‘This is the hole. We never turn the lights on here.’”

Maria wasn’t allowed to leave the cell for over a month, not even to take a shower or call her mother. “I feel like I’m losing my mind,” said Maria. It scared her when the adults in the other cells screamed and fought. One prisoner had stuck an arm through the hole in the door to try to touch her. Another often told her about how she had killed her own children.

“We’ll do whatever it takes to get you out of here,” said Javier.

Demands for change

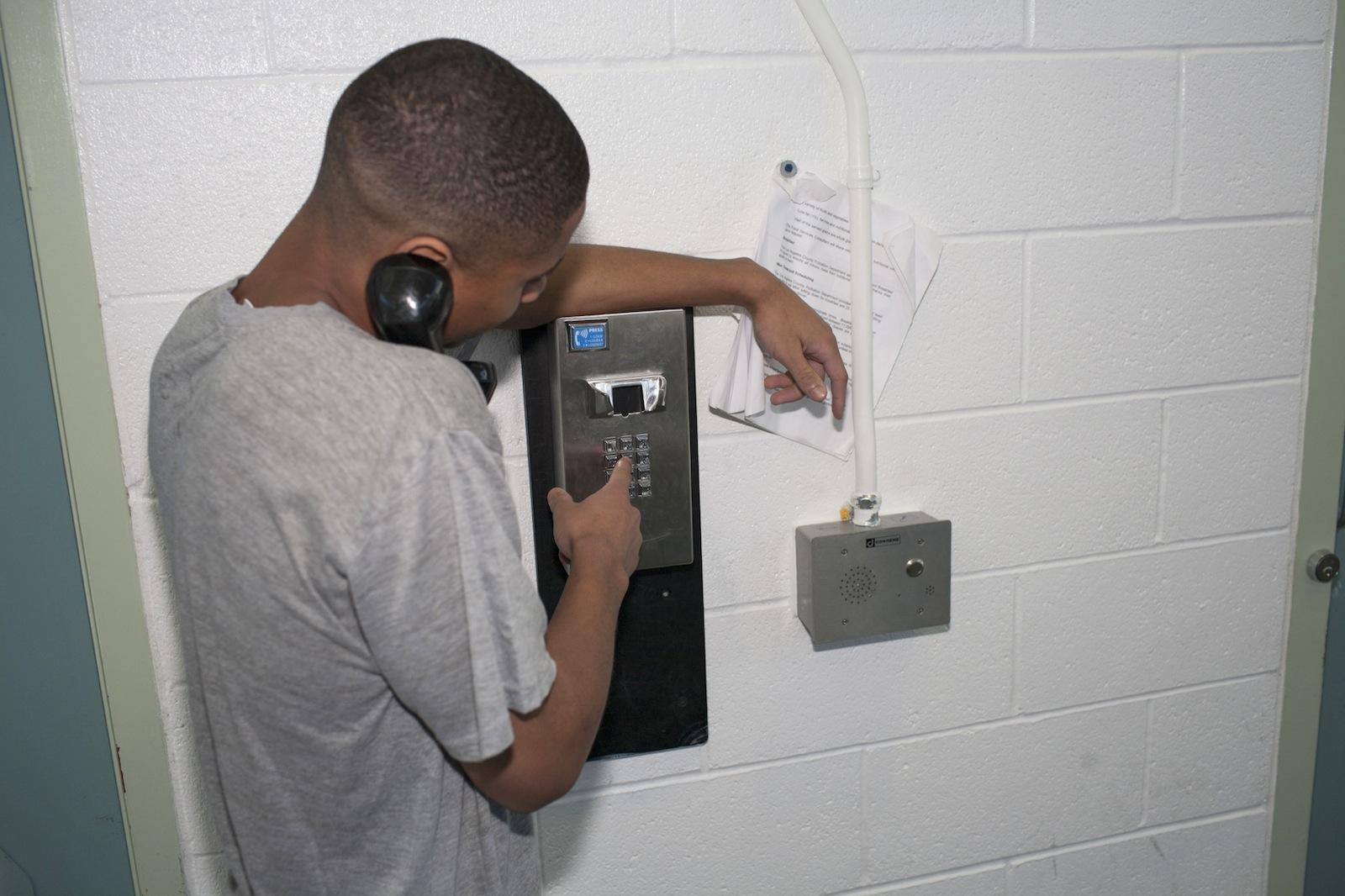

Javier protested to the prison management, but they said they had to keep Maria in isolation. In an adult unit she could be abused, even raped. Javier got hold of a lawyer who promised to try to help Maria. Then he also demanded to visit the boys, who were being held in a different part of the prison. There were so many of them that the prison had created a special child unit with around 40 windowless isolation cells. The boys were kept locked up for at least 23 hours a day, and were only allowed to come out to shower and call home from time to time. For a total of three hours a week they were permitted to walk around in a small cage on the roof, one at a time, to get some daylight and exercise. Now and again a teacher appeared and stuck some worksheets through the bars.

Javier and many others – prison chaplains, youth organisations, judges and lawyers – protested against this inhumane treatment. The lawyer who helped Maria eventually managed to get her moved back to the youth detention center. But the boys remained in the prison, and Javier watched as they became thinner, paler, and quieter. He tried to get the biggest newspaper in LA to write about it, but they didn’t think their readers were interested in children who had committed crimes. Months turned to years. And one day, the unthinkable happened. Two 14-year-old boys tried to hang themselves in their cells, but were rescued just in time.

Not welcome anymore

Javier had had enough. He called a press conference right outside the prison, and now, at last, the journalists came. “What is being done to children in this jail is sinful,” said Javier. The next day the prison staff called him and said, “You’re not welcome here anymore”. They were angry because Javier had promised not to tell anyone what went on in the prison. But Javier had got permission from the children and their parents. He sued the prison for violating his right to free speech. After two years, Javier’s case was upheld in court. The prison changed their rules and allowed him to visit the children again. Shortly thereafter the boys unit was closed down, and a decision was made that nobody should be moved to an adult prison until they are adults.What happened to Maria?

For a long time Maria had to stay in the detention center care unit. Seven months later, she was released and her mother picked her up. “I rode on the floor of the van and told my mom to check her rear view mirror. I said: ‘Mom, look back, they’re gonna come and get me.’ It was very hard getting used to people. And still, years later, I have a problem with cramped spaces.” Maria later graduated from high school and Javier helped her get her gang tattoos removed. Today she works at a restaurant and she is involved in the ‘Baby Elmo’ project, which helps incarcerated teenage parents learn to take responsibility for their children. “I go and talk to the mothers and tell them that we have to break the cycle. Nothing is more important than education. I have two children and my biggest fear is that they make a mistake like I did. My kids are not going to be in the street life, they are going to school.”Two 14-year-old boys tried to hang themselves in their cells, but were rescued just in time.

Always the outsider

Javier was born in Los Angeles, but moved to Mexico when he was nine. Soon after that his father died, and Javier felt like an outsider in his new country. He was the American, the ‘gringo’, who didn’t speak good Spanish. Everyone else at school had a dad at home. During his teenage years, Javier started hanging out with older boys who started fights in town to prove how tough they were. When he was 19, his family moved back to Los Angeles. “Suddenly I was a Mexican immigrant in the US,” says Javier today. “I always felt like an outsider. I think that’s why I could understand the children in jail. When they told me about feeling alone and vulnerable, I realised they weren’t so different from how I was as a child.”

Javier’s mother was the one who thought he should visit kids in prison. She was a volunteer at her church and thought some voluntary work would do Javier good. At the time he was working as a salesman in the jewelry business. “It didn’t make much sense to me,” says Javier. “Giving up my weekends to go to jail when I could be at the beach or watching football on TV. And I was scared. I had seen those kids on the news, gang members killing innocent folks.”

Eye-opener

Javier was nervous before his first visit, but soon he was visiting the kids several times a week. “The real eye-opener was accompanying kids to court. I had gotten to know them and their stories of loss and pain. To sit next to them when they got 75 years in prison was shocking. I felt I owed it to them to fight for their rights.” A few years later, Javier quit his well-paid job. “It didn’t work, first meeting with other jewlery dealers who would complain about not making enough million dollars in sales. Later in the evening, I would try to comfort a 14-year-old who had just found out he would spend the rest of his life in prison. I felt I had to use my time and energy on what felt meaningful.”

Creating justice

These days, Javier runs his own organization and fights for restorative justice. This means trying to create justice by ‘repairing’ the damage done using methods other than punishment, such as dialogue, education, and community service. “It is important to reach out to everybody who is impacted by crime,” explains Javier.“One of our most important activities is to organize healing dialogues with family members of victims of violent crime and of incarcerated youth. We have groups where mothers whose children have been locked up for life sit with mothers who’ve had children murdered. They have all lost their children, and when they share their stories and pain they can understand and console each other. It is very powerful.”

Since Javier became a director, he has had to attend a lot of meetings, meet with politicians and academics, and do lots of paperwork. But he will never stop visiting incarcerated children. He is grateful for his wife and three children, who support him even though their father often spends his evenings and weekends in jail.

“It is the relationships with the incarcerated children and their families that keep me going, it fuels everything I do. They need to know that I and many others fight for them and a better future. That they are not forgotten.”

Children locked up with adults

In the USA, around 250,000 children are tried as adults every year, instead of having their cases heard in a child and youth court. Every night, 10,000 children spend the night in an adult jail. Many of them have not even been tried, but are just suspected of a crime. Still, they are put in great danger and run a much higher risk of being subjected to abuse and sexual violence than adults in the same prisons. There is also a higher risk that these children will be affected by depression and attempt suicide compared to adults.

Colour matters

In the USA, the risk of being arrested and imprisoned is much higher if you are Black (African American) or Latine (with roots in Central or South America), or if you are an indigenous American. It’s much easier for white children to avoid arrest and conviction than children of other ethnic backgrounds, even if they have committed the same crimes. This is the case for everything from skipping school and graffiti, to violent crime. The risk is the highest for black children, who are nine times more likely to be sent to prison than white children who commit the same crimes, while Latino children are four times more likely to be imprisoned.

Text: Carmilla Floyd Photos: Joseph Rodriguez

Boys in a youth detention centre standing up for the Count. Photo: Joseph Rodriguez

Colour matters

In the USA, the risk of being arrested and imprisoned is much higher if you are Black (African American) or Latino (with roots in Central or South America), or if you are and indigenous American. It’s much easier for white children to avoid arrest and conviction than children of other ethnic backgrounds, even if they have committed the same crimes. This is the case for everything from skipping school and graffiti, to violent crime. The risk is the highest for Black children, who are nine times more likely to be sent to prison than white children who commit the same crimes, while Latino children are four times more likely to be imprisoned.

Children locked up with adults

In the USA, around 250,000 children are tried as adults every year, instead of having their cases heard in a child and youth court. Every night, 10,000 children spend the night in an adult jail. Many of them have not even been tried, but are just suspected of a crime. Still, they are put in great danger and run a much higher risk of being subjected to abuse and sexual violence than adults in the same prisons. There is also a higher risk that these children will be affected by depression and attempt suicide compared to adults.

Text: Carmilla Floyd Photos: Joseph Rodriguez

Related stories

Långgatan 13, 647 30, Mariefred, Sweden

Phone: +46-159-129 00 • info@worldschildrensprize.org

© 2020 World’s Children’s Prize Foundation. All rights reserved. WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE®, the Foundation's logo, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PARLIAMENT®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S OMBUDSMAN®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRESS CONFERENCE® and YOU ME EQUAL RIGHTS are service marks of the Foundation.