in prison

Michael is serving a life sentence without the possibility of parole at Calipatria prison. This is his story:

“I was raised in poverty like many kids in my circumstances. My mom was an alcoholic and my father was an abusive drug addict. But my dad went away, and eventually me and my siblings were taken away by CPS (Child Protective Services) and placed in care.

My grandmother took us in before they separated us into different homes. My mom wanted to take us all back, but my grandma only let her take my little brother and me. We went with my mother to live in absolute poverty in a ghetto, a gang, and a drug-infested neighborhood. We lived in a trailer with no windows, just clear bags to make it look like windows. The roof and floor were caving in, and the doors had no handles because they’d get kicked in by the cops anyway. My mother would leave me and my little brother by ourselves for weeks at a time. Our main source of food was going to school to get free breakfast and lunch. On the weekends I’d take my brother to the park where they gave meals to the homeless every Sunday. Eventually, I had to start stealing to take care of us, to get clothes and food. My mom started staying home more often when I was about 10 years old. She didn't like that I was stealing to put food on the table. So she would kick me out. From then on I lived mainly on the streets.

Learnt to survive

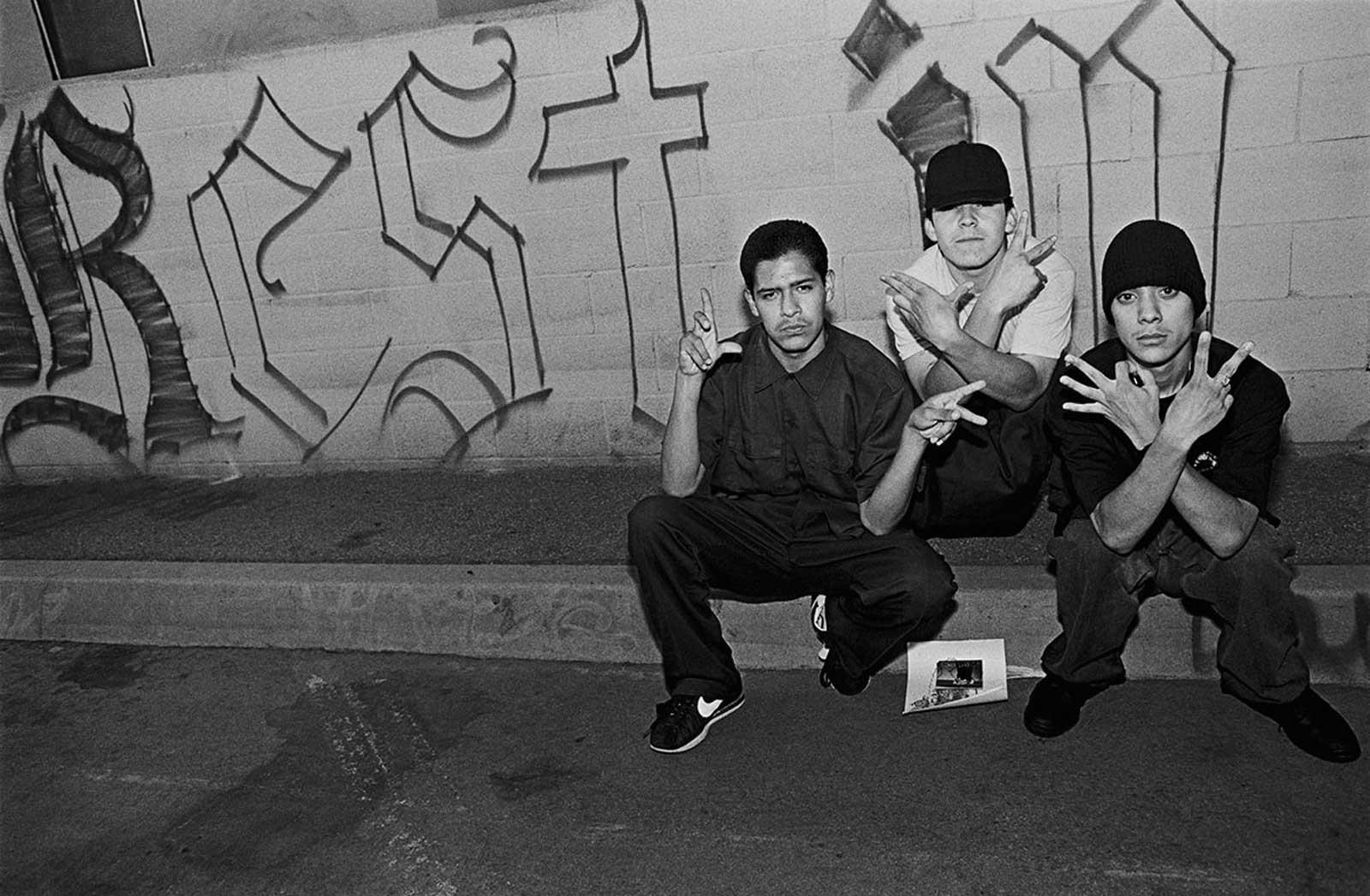

I got jumped into the gang at the age of eleven. The gang taught me how to make money by robbing and selling drugs. We had enemies who wanted to kill me or someone I loved. I learned to hate them so much that I lost sight of who I was. I didn't care about money anymore. I just wanted to hurt them as much as I could for every time they jumped me or shot at me or killed people who were close to me.I started using heavy drugs like crack and meth. I became what people called a crackhead at the age of eleven. My mom wouldn’t take me in, so I slept in bushes, under bridges, and in park restrooms. My homies wouldn’t take me in either but they’d give me a gun and tell me to take care of myself.

Arrested for the first time

I lived on the streets until the age of twelve. Then, someone tried to shoot me from a car but I fired first and saved my own life. I was caught but only charged with discharging a firearm at a moving vehicle. After a short time inside, I was let out. My mom didn’t want me staying at her house so I was soon back in the hood, with my gang. I went out 10 times worse because I had seen jail and was no longer scared of it. I had a new outlook on life. I thought that if I can hurt as many enemies as I can, I could prevent them from hurting me or one of mine the next day. So I continued to inflict as much damage as I could. I lost contact with who I really was. Just a twelve-year-old kid.

War on the streets

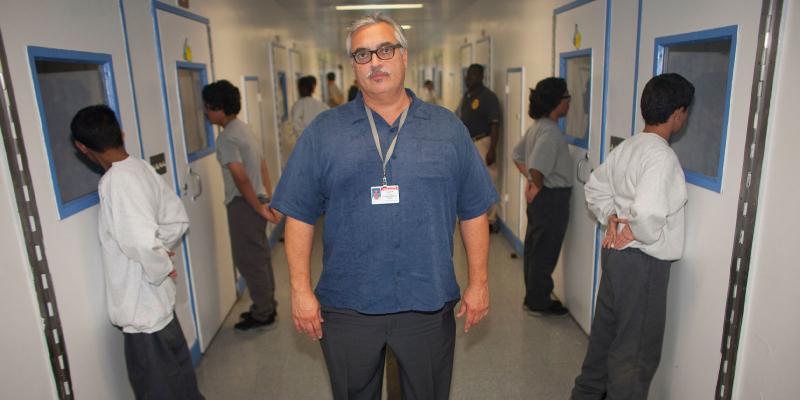

My parole officer was meant to keep an eye on me after I was released. He sent me to a group home because I was running the streets. I was in the group home system for two years before I ran away and started selling a lot of drugs. The streets were at war at the time, absolutely vicious. In that situation, innocent people are shot or killed at times. The nights are the worst, but violence can happen at any time of day. It makes you feel paranoid like someone is always following you around. I didn’t even feel safe walking to the store without a gun. I was arrested by the police for selling drugs and carrying a gun. I went to Juvenile Camp for six months, where I ran into guys from other gangs who had shot at me and who I had shot at. We fought every time we saw each other – like animals tearing at each other's throats, never realizing that we were basically each other’s mirror images. We’d grown up in the same circumstances but hated each other because he lived three blocks from me. They released me at the age of 14. I had nothing, so I started selling drugs again within two weeks and my mom kicked me out again. I had sunk so low, I was in a deep dark place where I didn’t care about life, not mine or anybody else’s. I found a release for my anger and frustration through hurting others. So many nights I slept under that bridge. I cried to myself – not understanding life. Confused, cold, and heartless. I unleashed all those feelings on people I felt were the enemy.They released me at the age of 14. I had nothing, so I started selling drugs again within two weeks and my mom kicked me out again.

Caught again

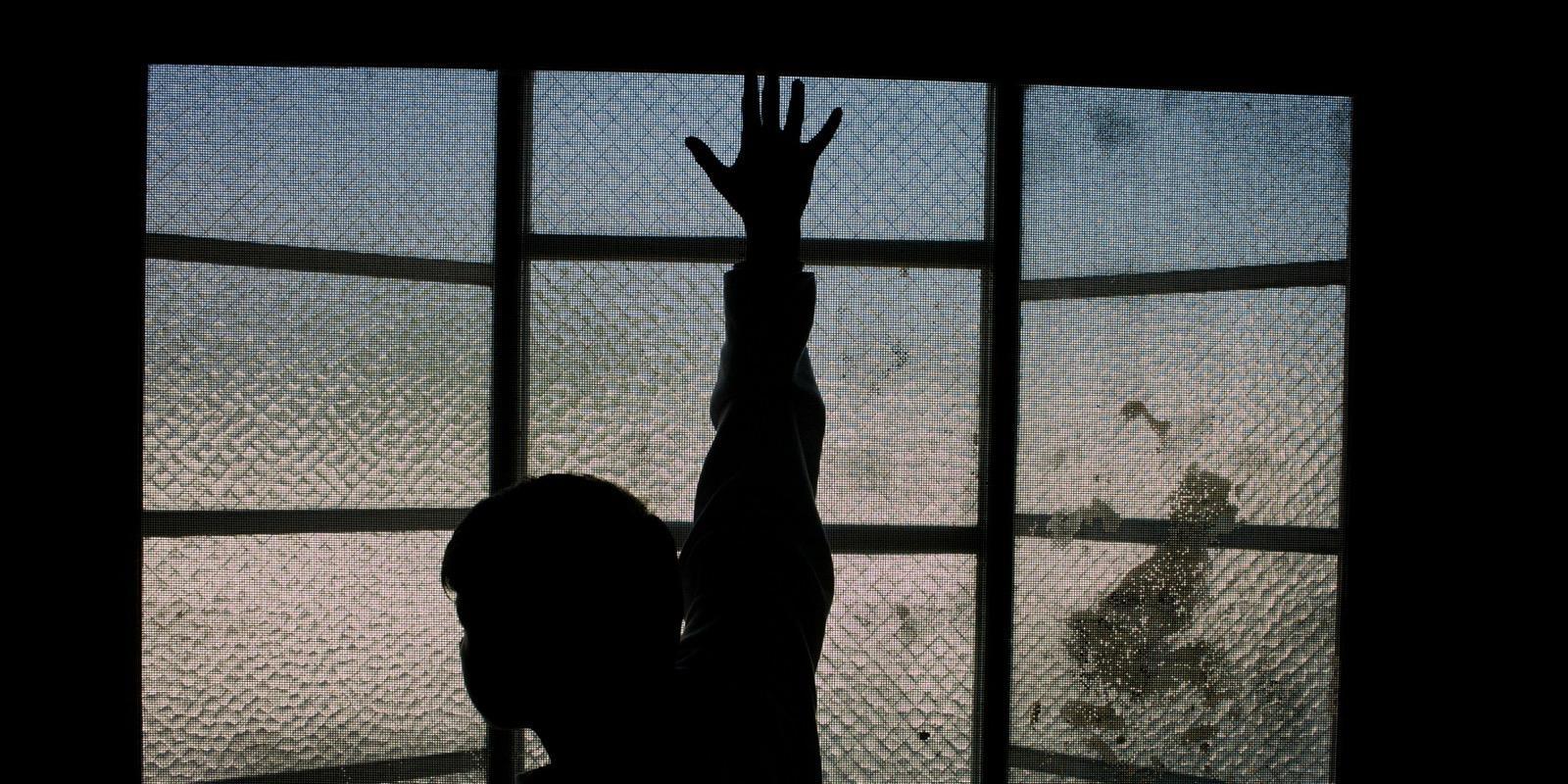

Three months after I turned 15, I was arrested on five attempted murders. My crime partner, who was older than me, blamed everything on me because he thought I’d get less time. It was decided that I should be sentenced in adult court. I had everything stacked against me: Two women, who were among the victims testifying against us; my crime partner telling on me; ‘gang experts’ pointing at me; my public defender who didn’t want to defend me because of the severity of the crime. Every night after the trial I would get into fights in juvenile hall because I didn’t care anymore. But I remember one time after they had thrown me in the ‘box’, the isolation cell, for fighting with staff. I suddenly thought to myself; “Nobody is doing this to me. I’m doing this to myself. If this is going to be my home for the rest of my life, why make it worse than it already is.” I started to read books and found ways to keep busy, like watching movies. I love to read about all the different places where I’ve never been. Things I’ve never seen. Learning about how people struggle in other countries that are way worse than mine. Education is the key, I think.

Sentenced to life

I wasn’t surprised when I got a life sentence. I told my mom when she visited me a week before I was convicted: ‘Don’t let them see you cry in there’. That day I walked into the courtroom, hoping the jury had not been able to agree, knowing that it wouldn’t happen. When they said ‘Guilty’ for the first attempted murder, I put my head down, knowing my fate had been sealed in stone. But then I picked my head up, refusing to let them see me lost. I smiled to show them that they could not break me. But I cried after when they took me back to my cell because I knew my future. Now I feel stronger than I’ve ever been. New laws are coming to help kids like me. Some of us never knew we had any other choice but to live the life we lived. Maybe it took the worst for us to realize that we can make the best out of this worst. When you no longer have anything to lose, you have everything to gain. As long as you don’t sit there feeling sorry for yourself. We all have something that makes us happy. We can help ourselves.”

Facts on LA gangs

Michael joined a gang in Los Angeles (LA) when he was eleven. Gangs have existed in LA since the 1940s. It all started with groups of white racists who went to Mexican American areas and attacked young people there. The police didn’t do anything about it, so lots of young Latinos joined with their friends to defend one another and their neighbourhood. Gradually, some of the gangs of friends started to fight with one another, about which neighbourhood was best and who was the strongest. Some developed into criminal gangs, who fought over who was allowed to sell drugs in particular areas.In the 1980s, many gangs started using more weapons and selling more dangerous drugs. In recent years crime has decreased, but there are still hundreds of gangs all over LA, from all different ethnic groups. Many children who grow up in gang neighbourhoods often feel forced to join, to gain friends and protection. Once you have joined, it’s hard to leave without being punished. Many high- ranking gang leaders have been sentenced to life in prison, but continue to run their gangs from inside.

Did you know?

• Out of all those serving life for murders committed when they were children, almost half were not physically involved – for example, by firing a weapon. Some were standing alongside the person responsible. Others were look-outs, for example, outside a shop, while their friends carried out an armed robbery.• In cases where the child had an adult crime partner, the adult received a shorter sentence than the child in more than half of cases. • That 85 percent of people in California who have been sentenced to life imprisonment for crimes committed when they were children, are black (African American) or Latino. Text: Carmilla Floyd Photos: Joseph RodriguezRelated stories

Långgatan 13, 647 30, Mariefred, Sweden

Phone: +46-159-129 00 • info@worldschildrensprize.org

© 2020 World’s Children’s Prize Foundation. All rights reserved. WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE®, the Foundation's logo, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PARLIAMENT®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S OMBUDSMAN®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRESS CONFERENCE® and YOU ME EQUAL RIGHTS are service marks of the Foundation.