Like many other Haitians, Guerline and her family lived across the border in the Dominican Republic. She went to school there and her parents worked, but they didn’t have a work permit. One day, the country’s president started talking about sending all Haitians without a work permit back to Haiti ...

Guerline heard on the radio that the president of the Dominican Republic said he didn’t want people from neighbouring Haiti living and working in his country.

“Yeah, yeah, but no-one’s going to listen. He’s just

talking a load of rubbish,” explained Guerline to her

little brother.

Both her dad Edmond and her mum Anita are from Haiti, but they met in the Dominican Republic. Her dad had travelled there to work in construction and sometimes in the fields. Her mum was there working as a housekeeper.

When Guerline was six years old, she started school in the Dominican Republic and learned Spanish. At home the family spoke Creole, which is the language of Haiti.

The Dominican Republic and Haiti share the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean. The border between the two countries stretches across mountains and forests with bad roads. Many Haitians travel across the border every year to work in the neighbouring country, with or without a work permit. They work on farms, construction sites, at tourist hotels and in the homes of people with a bit more money, who want someone to take care of their children and household.

Few people thought that the president of the Dominican Republic would suddenly throw all the Haitians out, but this time he was serious.

Deported by police

One Friday, Guerline was on her way to a friend’s house. She saw a police car outside her home, where her mum was. She didn’t think anything of it, but one of the policemen called out:“Hi, where are you from?”

“Hi, I’m from here,” answered Guerline.

“But were you born here? Are you from the Dominican Republic?” asked the policeman.

“Well, I was born here, but my parents are from Haiti.”

“What do your parents do?”

“They work.”

“Are they at home right now?”

“Yes, my mum is.”

The policeman asked Guerline to show them where she lived. He asked her mum Anita if she had a work permit.

“No,” she replied.

“Then I’m sorry, but I have to deport you,” said the policeman.

“What, now? Right away?”

“Yes, you have to get in the car and we’ll drive you over the border.”

Back in Haiti

Just a few minutes before, Guerline’s younger siblings had gone over to a neighbour’s. The police didn’t ask if there were any others in the family, they just took Guerline and her mum with them.At the border, the police made sure Guerline and Anita went back to Haiti through the high black gates. They were met by staff from the UN and Haiti’s social services, who asked whether they needed help with anything.

The UN employee took them to a young woman in a blue T-shirt displaying the words ‘Zanmi Timoun’.

“I can help you,” she said.

The woman explained that she worked at the border every day. Her organization Zanmi Timoun takes care of children who are deported.

“But since you have a relative you can live with, I can see that you don’t need that much help,” said the woman.

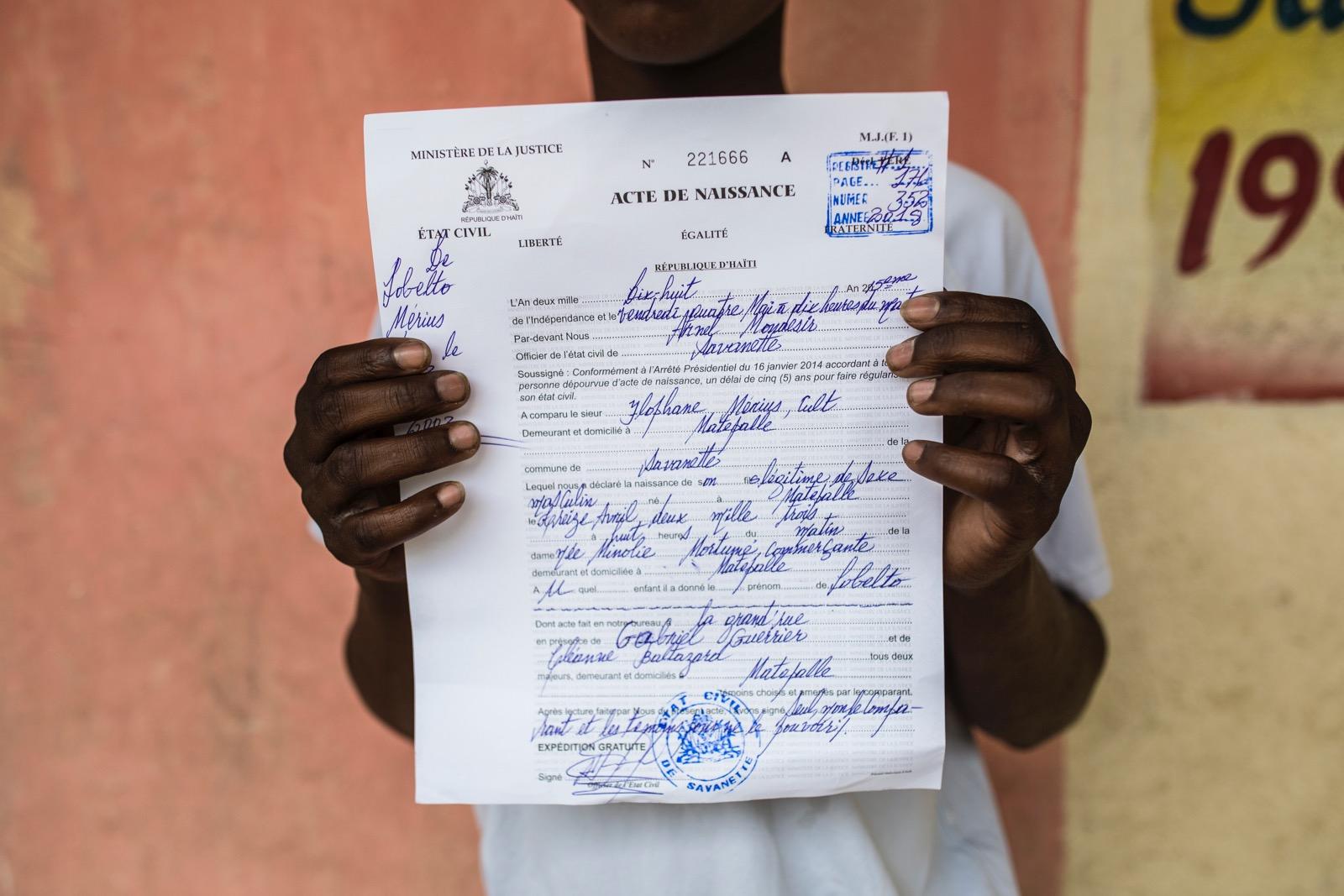

She explained that many children who are deported don’t have a birth certificate, passport or contact details for a relative in Haiti. That’s when Zanmi Timoun steps in to help find a relative. And they can sort out birth certificates.

“We were given underwear, soap, washing powder and toothbrushes. Zanmi Timoun even paid for a motorbike taxi to take us to my aunt’s house.”

Sometimes, Guerlain dreams of leaving school and just engaging in music.

Starting school

The next day, the young woman knocked on the door of the aunt’s house. She explained that the best thing for Guerline would be for her to stay in Haiti and finish school. She said that it would be best for her three younger siblings to also come home to Haiti and go to school there. Zanmi Timoun would make sure they all got school uniforms and a place in school.A few days later, the whole family were reunited apart from Guerline’s dad. Her dad carried on working in the Dominican Republic and sending home money for the family.

Guerline’s relatives gave the family a bit of land and helped them build a house. Zanmi Timoun helped by providing some building materials.

Many of the pupils in the school have lived in the Dominican Republic, like Guerline. They are all struggling to learn both Creole and French. During breaktime they still speak Spanish sometimes, as they do in the Dominican Republic.

When her mum Anita crosses the border to the Dominican Republic to sell garlic, Guerline looks after her siblings at home. Then she helps sell the potatoes that mum buys in the neighbouring country.

Sometimes Guerline wishes she could bunk off school, and get away from homework and her siblings. She just wants to listen to music, dance and play instruments. She’s learning to play the trumpet at a neighbour’s.

“One day I’m going to be as famous as Shakira,” says Guerline.

"With this birth certificate, I can finally move as I please. I don't have to worry about being expelled from the school! It feels very good. .When I do not go to school, I help mom work on the field or I play football.

Roberto, 15 years old

Right to an identity

In Haiti, many children never come into contact with the authorities when they are born, and they have no birth certificate. They grow up with a name, but without any papers to prove when and where they were born, and who their parents are. You need a birth certificate in order to go to school. You also need it if you want a passport to travel or work. Zanmi Timoun helps children get a birth certificate. They talk to children’s parents about how important it is for their child to be part of Haitian society, and that as children they have the right to their own identity and to go to school. The work to help children get birth certificates involves cooperation with the Haitian government and UNICEF. The certificates are often presented at special ceremonies out in the villages. Getting your own identity is a big thing.Haiti’s migrants

More than two million Haitians live abroad. Half of them live in the US and almost as many live in the Dominican Republic, but there are also Haitian migrants living in Canada, France, Brazil and Chile. In 2015, almost 52,000 Haitians were deported from the Dominican Republic. Over the following two years, more than 200,000 Haitians returned home from the Dominican Republic. Tens of thousands of impoverished Haitians who left the Dominican Republic are living in extremely poor conditions in temporary settlements in southeast Haiti. After the earthquake in 2010, some 60,000 Haitians were given temporary residence permits in the US, but President Donald Trump has said that they must return home by 2019. A third of Haiti’s gross national product (GNP) consists of money that Haitians living abroad send home to relatives in their home country.Related stories

Långgatan 13, 647 30, Mariefred, Sweden

Phone: +46-159-129 00 • info@worldschildrensprize.org

© 2020 World’s Children’s Prize Foundation. All rights reserved. WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE®, the Foundation's logo, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PARLIAMENT®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S OMBUDSMAN®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRESS CONFERENCE® and YOU ME EQUAL RIGHTS are service marks of the Foundation.