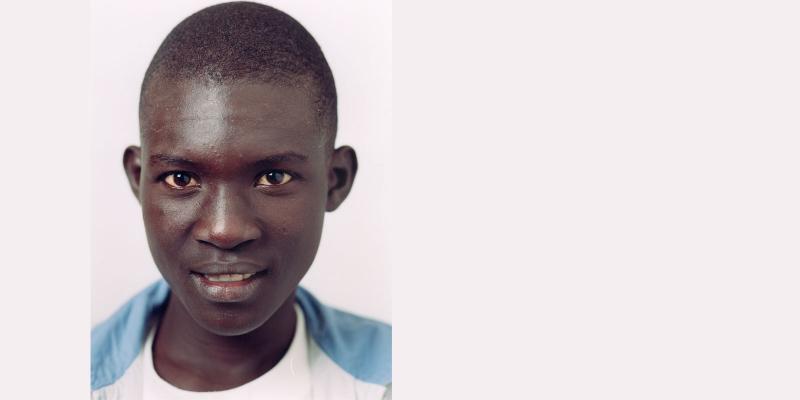

Ananthi from South India represents children at risk of being forced into child marriage and girls at risk of being killed at birth.

Ananthi can’t remember how old she was when one day her mother said: “We were planning to kill you, but we let you live.” Around the same time Ananthi found out that she had a sister, who was buried right beside their house, under the jasmine bush.

“That could have been me,” thinks Ananthi. Sometimes she sits there and talks to her sister, when there’s nobody around. She doesn’t want to make her parents feel sad or guilty.

“Don’t be angry,” whispers Ananthi. “Dad wanted to kill me too. He didn’t know any better back then.”

Ananthi’s birth was celebrated with a party in the village. The women’s group gave her two coconut trees and two goats. The family sell the goats’ milk and the money has made a big difference, especially since Ananthi’s father injured his back, making it hard for him to work.

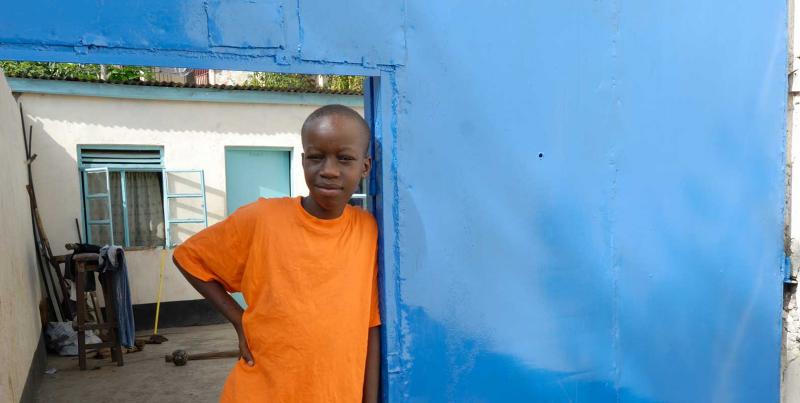

Annandhi loves to take of the goats’ kids, especially after the mother goat died.

Ananthi becomes a ‘mother’ A few months ago the goats had kids. The mother goat was old and she died giving birth, so Ananthi became the kids’ new ‘mother’. She gave them milk, and lots of love. Now the kids don’t need her any more, except one. Ananthi calls her Shri, which means ‘holy’. Shri is poorly, and isn’t growing the way she should. She follows Ananthi wherever she goes, even to school. Her mother and father don’t love Shri in the way Ananthi does, but they do want her to survive. Unlike the male kids, Shri can give the family milk and new kids in the future. “It’s not logical,” thinks Ananthi. “Adults only want to have sons, and they kill their daughters. But it’s the other way round with animals. Female animals, like cows, are the valuable ones. The bulls are killed and eaten. Why can’t people see that a girl is valuable? She can take care of her family just as well as a boy, maybe even better. I hate that attitude. I’m going to go far, to show that all girls have value and right to live.”

The family’s home has large holes in the wall and ceiling that they can’t afford to repair. When the monsoon rains come, the house leaks.

Hard to sleep The family’s home has large holes in the wall and ceiling that they can’t afford to repair. When the monsoon rains come, the house leaks. Everything gets wet and the mud walls start to split. Once when Ananthi was nine, a chunk of the wall fell on her head while she was sleeping. Since then, she has been afraid of the house collapsing. Ananthi often lies awake, wondering how her family will survive until she and her older sister finish their education and start to work. One night, after overhearing an argument between her parents about money, she doesn’t sleep a wink. Her tears fall in the darkness, but when her mother comes in she pretends to be asleep. The following morning she sits down at the jasmine bush and whispers: “If they had let you live and killed me instead, you would be suffering as I am. At least you’re safe now.” Then she goes to school, with Shri the goat kid pattering along behind her.

Men making problems There’s no school in the village. Ananthi and her friends walk a few kilometres to the school in a neighbouring village. On the way they see a group of men who shout: “Come and dance with us!” It is common for men to try to talk to the girls on their way to school. Sometimes they follow them and pull at their clothes. Ananthi’s mother has told her to scream and fight if she is attacked. That used to be unthinkable. Before, a girl could never say no to a man. If a girl was attacked, it was always her own fault. That was one of the reasons why girls couldn’t go to school – their parents were too afraid to let them go. Ananthi has a good day at school, and on the way home she is happier. She tells her father that the teacher praised her. “You are so talented!” he says. “I can’t imagine that you would not have been here with us.”

Annandhi goes to the local night school, which is run by the village’s women’s group.

Every evening Ananthi goes to the local night school, which is run by the villagers. The mothers from the women’s group help out with homework and organise games, plays, singing and dancing. Both boys and girls learn about their rights and that sons and daughters are equal. Before, in Ananthi’s village, almost all the men used to beat their wives – sometimes even to death. Nobody was ever punished for it. The boys took after their fathers and treated their sisters and other girls badly. Ananthi’s father used to drink and beat her mother too, but with the help of the women’s group she told him to stop. She threatened to leave him if he didn’t stop drinking and abusing her. And it worked!

Wedding can wait Ananthi doesn’t plan to get married until she is at least 25. First, she wants to finish her education and get a good job. “They might try to marry me off earlier, but I’ll fight it,” she says. “My husband must be kind, and share the housework. And his family are not getting a dowry. My education is my dowry! I’ll earn my own money.” These days, the tradition of killing baby girls has been almost completely eradicated from Ananthi’s village. In the area where she lives, thousands of girls’ lives have been saved in hundreds of villages, ever since their parents became aware of the importace of girls’ equal value, and came together to change age old traditions. “Now they know that girls are a gift, not a punishment,” says Ananthi.

Shri won’t wake up One morning, Shri the goat kid doesn’t come skipping over to Ananthi when she steps out into the garden. She has died during the night, and is lying cold and still under a tree. Ananthi can’t stop crying, although she knew that Shri was sick. The tears flow for two days, and she is very sad long afterwards. It feels like she has lost another sister, or a best friend. She sits down at the jasmine bush, with its strong sweet smell. “I never got to meet you,” she says to the sister under the ground. “If you had been allowed to live we could have played together and supported each other. In the future, if anybody has a daughter they don’t want, I will take care of her as though she was my own child.”

Långgatan 13, 647 30, Mariefred, Sweden

Phone: +46-159-129 00 • info@worldschildrensprize.org

© 2020 World’s Children’s Prize Foundation. All rights reserved. WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE®, the Foundation's logo, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRIZE FOR THE RIGHTS OF THE CHILD®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PARLIAMENT®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S OMBUDSMAN®, WORLD'S CHILDREN'S PRESS CONFERENCE® and YOU ME EQUAL RIGHTS are service marks of the Foundation.